Valerie Kabov investigates the global art market and what this means for the real market concerns in Africa. Kabov also talks to Marc Stanes of Ebony and Johans Borman of Johans Borman Fine Art about working with emerging and established artists from the African continent and the current global preoccupation with ‘youth.’

This article appeared in the inaugural September issue of ART AFRICA magazine, which was launched to enormous enthusiasm at the FNB JoburgArtFair 2015. You will also be able to read this exclusive content in the September Digital Issue (FREE app download here for Apple and here for Android).

This article appeared in the inaugural September issue of ART AFRICA magazine, which was launched to enormous enthusiasm at the FNB JoburgArtFair 2015. You will also be able to read this exclusive content in the September Digital Issue (FREE app download here for Apple and here for Android).

Presently, the art world finds itself at an interesting juncture. Over the past decade, the market for art – assisted by exponential advances in communications and technology – has become an overwhelming force, actively moving to shape, influence and change the face of contemporary art on a global scale. To many art world stakeholders, this shift signifies the end of the world as we know it – and for some, not in a good way. Interviews, articles and reportages bemoaning the state of the art market have become a staple of art media.

Concerns include the commercial nature of art fairs, that artists have been irrevocably corrupted by the new developments, the closure of more traditional galleries, the ‘new world’ of galleries where sales and money are the be-all and end-all and finally, a strong aversion to the new class of upstart collectors, who see art merely as an asset and who have been driving prices astronomically by ‘flipping’ the value of works by emerging artists. While most of these comments are earnest and reflect real concerns, it is useful to locate them in the context of broader art history to identify the real (as opposed to perceived) novelty. In this moment, the market finds synergy with important movements in art history.

Among this synergy is the rebalancing of the central and peripheral relationships in the art world – and building recognition for underexplored art scenes. The contemporary art scene in Africa is one such example of this rebalancing. This scene encompasses a particularly unique set of characteristics, and the manner in which it is approached and engaged with will determine whether this is truly a historical moment.

Even the scantiest view to art history will reveal, that the current ‘moment’ is far from novel. The Medicis, who were nouveau riche, consolidated their power and prestige with art and cultural patronage and commanded geniuses like Raphael, da Vinci and Michelangelo to do their bidding and interfere in ways that would seem monstrous today. And yet today we are thrilled to be mining history thanks to these very interventions. Superstar artists like Michelangelo and Leonardo were multi-millionaires in their time, traveling Europe on mega-commissions, wined and dined by the mighty of the world. Rembrandt, a saintly figure in the art canon, authorised his apprentices to paint his ‘self-portrait’ as a form of branding and advertising. In late 19th century Paris, Daniel Kahnweiler, another nouveau riche, began buying work in bulk for resale from artists he figured might have a future – Picasso, Cezanne and Matisse. Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose (‘The more things change, the more they stay the same.’)

There is, however, a historically significant shift that many are missing in their self-righteous protestations of ‘too much too-new money ruining art’ – that some of this market power really does come from new money. This is a major paradigm shift, because part of the self-titled ‘old guard’s discomfort is that the new money and new movements in the art world are shifting the centers of the art world beyond Paris, London and New York. That this new money punts and supports artists not from the West attests to lasting change in visual culture and its paradigms. Increasingly, artists and art sectors outside of the West are gaining exposure and recognition. Could it then be posited that they too are the ‘products’ of rampant globalisation, new money and the horror of art fairs?

If the market – by way of being the only mechanism with which to leverage valuable opportunities – is devoid of a moral compass, then it must be the responsibility of the historians, critics, curators and academics in (and interacting with) the sector, to maintain and preserve a sense of morality. The emergence of the contemporary art sector in Africa on the global stage is a case study of and an experiment in the symbiotic relationship between market and academia. As Mark Coetzee asserted in a panel discussion at this year’s Art Basel, “African art is currently in fashion.”1 African curators and academics have been building the foundations for engaging with the international art community for decades, confirming and validating the current opportunity. This groundwork comprises noteworthy exhibitions such as ‘Art from the Commonwealth’ in 1962 to ‘Magiciens de la Terre’ in 1989 and ‘Africa Remix’ in 2004, publications such as Nka Magazine and Revue Noire, initiatives like the Triangle Network, galleries like October Gallery and many other art professionals, curators, writers, historians and gallerists who have worked hard to advance the cause of art and artists on the continent.

However, as Coetzee also correctly pointed out, fashions come and go with predictable, and somewhat disappointing, regularity. So for now, while euphoria and optimism rule in African contemporary art, we need to make a sober analysis of what this present moment means and what is required of us to engender vibrant and successful art sectors.

This is a complex question with difficult answers as there are a number of crucial factors differentiating the spotlight on Africa from others and which can characterise its aftermath.

One of these factors is that – unlike most other art scenes touched upon by the global largess, such as Brazil, India, China and the Middle East – Africa (with the few exceptions of South Africa, Nigeria and Angola) does not have supportive domestic markets for contemporary art. The new money in the aforementioned foreign art markets comes from within – and is used to support and attract attention to their national art scene. When the prices for the (then) fad of Chinese contemporary art dropped and the temporary art market bubble burst circa 2008, an interesting thing happened – the prices dropped substantially only for those artists favoured by Western collectors. The prices for artists supported by local collectors remained stable, allowing for the rebuilding of the Chinese contemporary market, now a dominant sector in the art world only a few years later.

The same cannot be said about Africa. It isn’t an unrealistic assessment that African contemporary art is still largely supported by old money – or to put it another way – not enough of it is supported by new money. This lack of support is exacerbated by inadequate art infrastructure on the continent. These gaps in infrastructure have already created, and continue to contribute to, a talent and resource drain – not to mention that as a result many African contemporary art masterpieces will be lost to local audiences. Another vulnerability is that the global spotlight, with few notable exceptions, has been on emerging or young artists. While this focus on emerging artists is a global phenomenon, in the African context it is uniquely problematic – given the disparities in market and infrastructure outlined above.

Often, young artists move away from Africa in pursuit of educational and career opportunities. This relocation affects generational mentorship and local systems of support, as well as their own practice, which has to be reshaped in relation to a new context and the assumption of a new identity. Back in Africa, foreign galleries who sign African artists inevitably contribute to the drain on local talent and general economy, as the profits and commissions of their sales are circulated abroad. Significantly, without support systems at home or experience of international markets, young artists are more likely to be negatively impacted by market pressures and the related exploitative practices.

Concurrently, there are also gifted artists outside of the ‘golden youth’ spectrum who have simply been overshadowed in the market juggernaut. These artists may then feel helpless and hopeless in a way that their peers in countries with stable art economies and a culture of collecting do not. In an effort to build strong cultural identities – without which the emerging generation can only default to foreign learning and achievement – it is crucial that we recognise the broader context in which art develops and emerges. It is more than likely that the global market will, in due course, view mature artists in the West as yet another under-valued opportunity. However, when the global market reaches this realisation, it will have been neatly prepared for it by decades of institutional and academic support, along with substantial bodies of work. The African peers of such artists, who are currently in the shadows and bereft of institutional attention and publishing validation, could be left behind. This problem is not reserved only for the artists or the history of art in Africa.

Rather, it is a collective concern for global art history – the effort to shift the nexus cannot be the responsibility and product of one generation.

It is highly unlikely that there will be sufficient time to address these issues with market and infrastructure by the time the fashion moves on to wherever it will (if this year’s Havana Biennale is anything to go on). While Western galleries, who have turned to representing African artists, are able shift focus by taking on artists from whatever scene is next in vogue, galleries and artists on the continent can be left vulnerable.

Looking to history as a predictor, we could surmise that the countries on the continent with the strongest markets and infrastructure, who have already taken the lead in building private and public collections, will forge ahead in carving out their own niche in the global scene – leaving the rest to fend for themselves. And yet this is not the paradigm shift that so many have worked tirelessly to achieve. While for now ‘African Contemporary Art’ is a useful marketing term to those of us working in the field, it speaks to a broader vision and ethos of brotherhood on the continent, an ambition that supersedes mere market concerns.

Concerns include the commercial nature of art fairs, that artists have been irrevocably corrupted by the new developments, the closure of more traditional galleries, the ‘new world’ of galleries where sales and money are the be-all and end-all and finally, a strong aversion to the new class of upstart collectors, who see art merely as an asset and who have been driving prices astronomically by ‘flipping’ the value of works by emerging artists. While most of these comments are earnest and reflect real concerns, it is useful to locate them in the context of broader art history to identify the real (as opposed to perceived) novelty. In this moment, the market finds synergy with important movements in art history.

Among this synergy is the rebalancing of the central and peripheral relationships in the art world – and building recognition for underexplored art scenes. The contemporary art scene in Africa is one such example of this rebalancing. This scene encompasses a particularly unique set of characteristics, and the manner in which it is approached and engaged with will determine whether this is truly a historical moment.

Even the scantiest view to art history will reveal, that the current ‘moment’ is far from novel. The Medicis, who were nouveau riche, consolidated their power and prestige with art and cultural patronage and commanded geniuses like Raphael, da Vinci and Michelangelo to do their bidding and interfere in ways that would seem monstrous today. And yet today we are thrilled to be mining history thanks to these very interventions. Superstar artists like Michelangelo and Leonardo were multi-millionaires in their time, traveling Europe on mega-commissions, wined and dined by the mighty of the world. Rembrandt, a saintly figure in the art canon, authorised his apprentices to paint his ‘self-portrait’ as a form of branding and advertising. In late 19th century Paris, Daniel Kahnweiler, another nouveau riche, began buying work in bulk for resale from artists he figured might have a future – Picasso, Cezanne and Matisse. Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose (‘The more things change, the more they stay the same.’)

There is, however, a historically significant shift that many are missing in their self-righteous protestations of ‘too much too-new money ruining art’ – that some of this market power really does come from new money. This is a major paradigm shift, because part of the self-titled ‘old guard’s discomfort is that the new money and new movements in the art world are shifting the centers of the art world beyond Paris, London and New York. That this new money punts and supports artists not from the West attests to lasting change in visual culture and its paradigms. Increasingly, artists and art sectors outside of the West are gaining exposure and recognition. Could it then be posited that they too are the ‘products’ of rampant globalisation, new money and the horror of art fairs?

If the market – by way of being the only mechanism with which to leverage valuable opportunities – is devoid of a moral compass, then it must be the responsibility of the historians, critics, curators and academics in (and interacting with) the sector, to maintain and preserve a sense of morality. The emergence of the contemporary art sector in Africa on the global stage is a case study of and an experiment in the symbiotic relationship between market and academia. As Mark Coetzee asserted in a panel discussion at this year’s Art Basel, “African art is currently in fashion.”1 African curators and academics have been building the foundations for engaging with the international art community for decades, confirming and validating the current opportunity. This groundwork comprises noteworthy exhibitions such as ‘Art from the Commonwealth’ in 1962 to ‘Magiciens de la Terre’ in 1989 and ‘Africa Remix’ in 2004, publications such as Nka Magazine and Revue Noire, initiatives like the Triangle Network, galleries like October Gallery and many other art professionals, curators, writers, historians and gallerists who have worked hard to advance the cause of art and artists on the continent.

However, as Coetzee also correctly pointed out, fashions come and go with predictable, and somewhat disappointing, regularity. So for now, while euphoria and optimism rule in African contemporary art, we need to make a sober analysis of what this present moment means and what is required of us to engender vibrant and successful art sectors.

This is a complex question with difficult answers as there are a number of crucial factors differentiating the spotlight on Africa from others and which can characterise its aftermath.

One of these factors is that – unlike most other art scenes touched upon by the global largess, such as Brazil, India, China and the Middle East – Africa (with the few exceptions of South Africa, Nigeria and Angola) does not have supportive domestic markets for contemporary art. The new money in the aforementioned foreign art markets comes from within – and is used to support and attract attention to their national art scene. When the prices for the (then) fad of Chinese contemporary art dropped and the temporary art market bubble burst circa 2008, an interesting thing happened – the prices dropped substantially only for those artists favoured by Western collectors. The prices for artists supported by local collectors remained stable, allowing for the rebuilding of the Chinese contemporary market, now a dominant sector in the art world only a few years later.

The same cannot be said about Africa. It isn’t an unrealistic assessment that African contemporary art is still largely supported by old money – or to put it another way – not enough of it is supported by new money. This lack of support is exacerbated by inadequate art infrastructure on the continent. These gaps in infrastructure have already created, and continue to contribute to, a talent and resource drain – not to mention that as a result many African contemporary art masterpieces will be lost to local audiences. Another vulnerability is that the global spotlight, with few notable exceptions, has been on emerging or young artists. While this focus on emerging artists is a global phenomenon, in the African context it is uniquely problematic – given the disparities in market and infrastructure outlined above.

Often, young artists move away from Africa in pursuit of educational and career opportunities. This relocation affects generational mentorship and local systems of support, as well as their own practice, which has to be reshaped in relation to a new context and the assumption of a new identity. Back in Africa, foreign galleries who sign African artists inevitably contribute to the drain on local talent and general economy, as the profits and commissions of their sales are circulated abroad. Significantly, without support systems at home or experience of international markets, young artists are more likely to be negatively impacted by market pressures and the related exploitative practices.

Concurrently, there are also gifted artists outside of the ‘golden youth’ spectrum who have simply been overshadowed in the market juggernaut. These artists may then feel helpless and hopeless in a way that their peers in countries with stable art economies and a culture of collecting do not. In an effort to build strong cultural identities – without which the emerging generation can only default to foreign learning and achievement – it is crucial that we recognise the broader context in which art develops and emerges. It is more than likely that the global market will, in due course, view mature artists in the West as yet another under-valued opportunity. However, when the global market reaches this realisation, it will have been neatly prepared for it by decades of institutional and academic support, along with substantial bodies of work. The African peers of such artists, who are currently in the shadows and bereft of institutional attention and publishing validation, could be left behind. This problem is not reserved only for the artists or the history of art in Africa.

Rather, it is a collective concern for global art history – the effort to shift the nexus cannot be the responsibility and product of one generation.

It is highly unlikely that there will be sufficient time to address these issues with market and infrastructure by the time the fashion moves on to wherever it will (if this year’s Havana Biennale is anything to go on). While Western galleries, who have turned to representing African artists, are able shift focus by taking on artists from whatever scene is next in vogue, galleries and artists on the continent can be left vulnerable.

Looking to history as a predictor, we could surmise that the countries on the continent with the strongest markets and infrastructure, who have already taken the lead in building private and public collections, will forge ahead in carving out their own niche in the global scene – leaving the rest to fend for themselves. And yet this is not the paradigm shift that so many have worked tirelessly to achieve. While for now ‘African Contemporary Art’ is a useful marketing term to those of us working in the field, it speaks to a broader vision and ethos of brotherhood on the continent, an ambition that supersedes mere market concerns.

1 Panel Discussion, ‘Building Art Institutions in Africa’ Art Basel 2015.

1 Panel Discussion, ‘Building Art Institutions in Africa’ Art Basel 2015. Valerie Kabov in Conversation with Marc Stanes

Co-founder of Ebony, South Africa

Born in London, photographer and curator Marc Stanes now lives in South Africa. Following the success of his initial venture Ebony in Franschhoek, a gallery specialising in fine art and contemporary South African design, Marc was invited to curate and direct the newly formed Museum of Modern Art in Equatorial Guinea (2011). He now acts as Ebony’s main art advisor to their current spaces in Loop Street, Cape Town and Franschhoek.

Co-founder of Ebony, South Africa

Born in London, photographer and curator Marc Stanes now lives in South Africa. Following the success of his initial venture Ebony in Franschhoek, a gallery specialising in fine art and contemporary South African design, Marc was invited to curate and direct the newly formed Museum of Modern Art in Equatorial Guinea (2011). He now acts as Ebony’s main art advisor to their current spaces in Loop Street, Cape Town and Franschhoek.

Valerie Kabov: From the vantage point of a newcomer to South Africa, how do you view the changes taking place in the art market from an international art market perspective? Personally, having lived in Australia for a long time, my early impression of the South African art market (even 6 years ago) was that it was very similar to the Australian scene – established and secure but in many ways insular, protective of its parochial history and not that interested in international engagement. This has changed dramatically over the last few years.

Marc Stanes: Over the past ten years, the market in South Africa has evolved at a rapid pace, mirroring the general upswing in collecting internationally. Initially, more traditional or modern works appreciated rapidly due to increased buyer engagement, while the secondary market grew through powerful auction houses. Recently, contemporary works have been the focus, with the rapid expansion of new contemporary galleries into the market and the more established galleries gaining international prominence. Generally, local buyers have driven the market – however, there’s an increasing international presence, with works at Africa-focused auctions and South African galleries participating regularly outside of their own borders.

As someone who works with both emerging and established artists from the continent, you’re in a position to comment on the current global preoccupation with ‘youth.’ What particular aspects of this phenomenon do you think are particularly important for artists in Africa?

I think that ‘the time is right’ if you are a young artist currently working on the continent – never before has there been such a spotlight on Africa. However, given the international market’s considerable awareness of young artists, it’s increasingly important that the right advice is given and taken. Young artists have the advantage of offering a fresh and original voice but the associated issues, such as speculation and being taken advantage of can be a hindrance.

You have written much about art as an asset class. Have you had to revise your ideas on the concept in light of recent developments and trends in the market, especially in reference to the focus on emerging artists and phenomena such as flipping and speculation – which many say is here to stay? Is this fascination with emerging artists valid, or are collectors missing the opportunity with more established artists who have remained under the radar or underexposed?

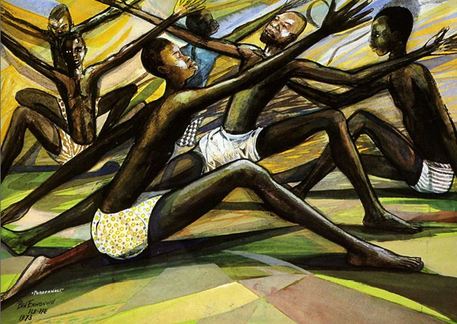

I’m not a great fan of speculation or buying art for investment. It detracts from the pleasure, interest and understanding in the artist and their process. It may be (or may prove to be) an increasing asset but there is no certainty. Speculation has always existed in the art market; it’s nothing new but some international artists and galleries have made efforts to combat this by applying artists’ resale rights and restrictions on subsequent sales and contracts. There is no doubt that the increasing appetite for ‘young’ art from the African continent fuels the above, but I do not wholly believe this is entirely detrimental to more established artists going forward. Increased awareness of art from the continent will filter across all segments. From a secondary market perspective, there is real growth from collectors acquiring pieces from the past fifty to hundred years, particularly in Nigeria. Many artists are being rediscovered, but currently there aren’t many outlets to view this work apart from auctions. Too many galleries and dealers are focusing solely on the ‘now’ and are missing out on a rich vein of history that has relevance to and influence on many young artists producing works today. Therefore, this does present an opportunity to the well-informed collector.

How do you think that African artists and galleries can best leverage the current ‘moment’ for contemporary art from Africa?

In many ways I think this is already being done. The obvious routes of good exhibitions, art fairs and partnerships with museums and other international galleries are important. Being insular is not an option. For the artist, having that original voice – which many artists from the continent already display – seems ‘fresh’ and exciting to the international market.

Given that most of the art sectors on the continent face infrastructural challenges, and that, with a few exceptions, local markets are unable to support artists’ livelihoods, we see more artists represented by galleries outside the continent, with some of the best art from Africa ending up in foreign collections. Do you see this as a problem and if so, what do you think can be done to begin remedying it?

I don’t fully agree with this and I don’t see it as much of a problem. Historically, this has been an issue on the continent, but the outcome has not been all bad. Many artists have left to pursue a career beyond their home borders, but some of the most important, influential and successful have stayed. Some have also returned. As economies on the continent improve and local interest in culture burgeons, artists are able to produce and sell to collectors within the continent as well as internationally.

Had certain major international collectors and museums not been interested in, exhibited or publicised their collections over the past twenty years, we would be in a different position today. It’s partly because of this initial international interest that artists have more opportunity to support themselves today. I also believe that there will be a growth in the number of institutions and galleries on the continent in the near future, but they may have to look to potential international partners in order to fund themselves properly.

Marc Stanes: Over the past ten years, the market in South Africa has evolved at a rapid pace, mirroring the general upswing in collecting internationally. Initially, more traditional or modern works appreciated rapidly due to increased buyer engagement, while the secondary market grew through powerful auction houses. Recently, contemporary works have been the focus, with the rapid expansion of new contemporary galleries into the market and the more established galleries gaining international prominence. Generally, local buyers have driven the market – however, there’s an increasing international presence, with works at Africa-focused auctions and South African galleries participating regularly outside of their own borders.

As someone who works with both emerging and established artists from the continent, you’re in a position to comment on the current global preoccupation with ‘youth.’ What particular aspects of this phenomenon do you think are particularly important for artists in Africa?

I think that ‘the time is right’ if you are a young artist currently working on the continent – never before has there been such a spotlight on Africa. However, given the international market’s considerable awareness of young artists, it’s increasingly important that the right advice is given and taken. Young artists have the advantage of offering a fresh and original voice but the associated issues, such as speculation and being taken advantage of can be a hindrance.

You have written much about art as an asset class. Have you had to revise your ideas on the concept in light of recent developments and trends in the market, especially in reference to the focus on emerging artists and phenomena such as flipping and speculation – which many say is here to stay? Is this fascination with emerging artists valid, or are collectors missing the opportunity with more established artists who have remained under the radar or underexposed?

I’m not a great fan of speculation or buying art for investment. It detracts from the pleasure, interest and understanding in the artist and their process. It may be (or may prove to be) an increasing asset but there is no certainty. Speculation has always existed in the art market; it’s nothing new but some international artists and galleries have made efforts to combat this by applying artists’ resale rights and restrictions on subsequent sales and contracts. There is no doubt that the increasing appetite for ‘young’ art from the African continent fuels the above, but I do not wholly believe this is entirely detrimental to more established artists going forward. Increased awareness of art from the continent will filter across all segments. From a secondary market perspective, there is real growth from collectors acquiring pieces from the past fifty to hundred years, particularly in Nigeria. Many artists are being rediscovered, but currently there aren’t many outlets to view this work apart from auctions. Too many galleries and dealers are focusing solely on the ‘now’ and are missing out on a rich vein of history that has relevance to and influence on many young artists producing works today. Therefore, this does present an opportunity to the well-informed collector.

How do you think that African artists and galleries can best leverage the current ‘moment’ for contemporary art from Africa?

In many ways I think this is already being done. The obvious routes of good exhibitions, art fairs and partnerships with museums and other international galleries are important. Being insular is not an option. For the artist, having that original voice – which many artists from the continent already display – seems ‘fresh’ and exciting to the international market.

Given that most of the art sectors on the continent face infrastructural challenges, and that, with a few exceptions, local markets are unable to support artists’ livelihoods, we see more artists represented by galleries outside the continent, with some of the best art from Africa ending up in foreign collections. Do you see this as a problem and if so, what do you think can be done to begin remedying it?

I don’t fully agree with this and I don’t see it as much of a problem. Historically, this has been an issue on the continent, but the outcome has not been all bad. Many artists have left to pursue a career beyond their home borders, but some of the most important, influential and successful have stayed. Some have also returned. As economies on the continent improve and local interest in culture burgeons, artists are able to produce and sell to collectors within the continent as well as internationally.

Had certain major international collectors and museums not been interested in, exhibited or publicised their collections over the past twenty years, we would be in a different position today. It’s partly because of this initial international interest that artists have more opportunity to support themselves today. I also believe that there will be a growth in the number of institutions and galleries on the continent in the near future, but they may have to look to potential international partners in order to fund themselves properly.

Valerie Kabov in Conversation with Johans Borman

Founder and director of Johans Borman Fine Art

A qualified structural engineer, Johans’ career as a gallerist began in 1989. Over the past thirty years his knowledge and love for modern and contemporary African art has grown exponentially – he metaphorically compares himself to a surfer selling surfboards. Johans managed galleries in Pretoria, Onrus River and Stellenbosch before opening Johans Borman Fine Art in Cape Town, in 1999.

Founder and director of Johans Borman Fine Art

A qualified structural engineer, Johans’ career as a gallerist began in 1989. Over the past thirty years his knowledge and love for modern and contemporary African art has grown exponentially – he metaphorically compares himself to a surfer selling surfboards. Johans managed galleries in Pretoria, Onrus River and Stellenbosch before opening Johans Borman Fine Art in Cape Town, in 1999.

Valerie Kabov: You have worked as a gallerist and art advisor for several decades. In this time, South Africa has undergone historic changes, as has the art market. What would you say have been the three key changes in the South African art market – especially in its relationship with the international art community and market?

Johans Borman: During the apartheid era, South Africa was in cultural isolation. From the 1990s, our new democracy made it possible for South African artists to travel and exhibit internationally. This meant that local artists, curators, academics and students had the opportunity to experience international art trends and influences. From the mid-1990s, worldwide Internet access was the next major factor to counter South Africa’s cultural and geographic isolation. South Africa’s newfound democracy and political freedom meant international acceptance, which had a very positive influence on the local art market. It instilled confidence in South Africa’s future and brought new interest from local and international collectors and curators. The local art market expanded rapidly as new galleries opened, and the auction market boomed until 2001, when the 9/11 attacks stalled world markets.

So you don’t see the current focus on African contemporary art as a key change?

The South African contemporary art industry has experienced tremendous growth since the early 2000s, coinciding with the new international interest and focus on contemporary African art. The choice of the Zeitz Museum of Contemporary African Art to open in Cape Town reflects this sentiment and will potentially establish Cape Town as the future art capital of Africa.

You have written much about art as an asset class. Have you had to revise your ideas on the concept in the light of recent developments and trends in the market, especially in reference to the focus on emerging artists and phenomena such as flipping and speculation – which many say is here to stay? Is this fascination with emerging artists valid or are collectors missing the opportunity with more established artists who have remained under the radar or underexposed?

My views on living with and collecting art have not changed. I don’t see art as a typical financial investment instrument, as it’s not created to be that in the first place. We should never forget – art is about life and the art market is about money. Unlike conventional financial investments, art does not pay dividends, interest or rent. The ‘return on investment’ is the result of the interaction with a work of art – it lies in the emotional stimulation and ‘cerebral gymnastics’ experienced during this appreciation process.

In my opinion, the concept of ‘investment art’ or art as an asset class distracts from the real purpose of art. The concept is emphasised to motivate non-art lovers to spend more money in the ‘art industry,’ trusting that they will realise a healthy profit. This concept is largely promoted by auction houses and profit-driven dealers who create environments where speculation and flipping thrive. They don’t feel any responsibility towards maintaining a healthy and stable market – their sole objective is to realise a profit. These factors are definitely not beneficial to the careers of contemporary artists, as their livelihoods depend on a stable, long-term market for their work.

Contemporary art and emerging artists enjoy much publicity – particularly because most art fairs and publications focus on the contemporary market and are designed to promote the latest and ‘hottest.’ However, the reality is that the bulk of overall sales (in financial terms) come from the more established artists and works by artists from the Modern era. This confirms that seasoned collectors are still spending much more to own works by established, ‘branded’ artists who have a proven track record (in terms of prices and value.)

What about in the context of artists from across Africa coming to South Africa? My personal view is that it is a double-edged sword, in terms of career development and creativity. What is your view of this phenomenon?

Historically, artists have migrated to wherever they can establish sustainable careers. If not in their home countries, they will relocate to where they have an audience and buyers or collectors.

Art fairs have become the mainstay of the art market – a key channel to market. As a gallerist with an established practice and collector base, do you feel pressure to participate in these events?

The success of art fairs lies in the fact that they provide artists and galleries the opportunity to collectively generate public interest for (mostly) contemporary art. Art fairs, along with apps like Artsy, provide a one-stop opportunity to see and engage with the international art buying fraternity.

This one-stop opportunity does, however, come at an enormous cost. To make art fairs feasible, the additional costs of hosting, organising and publicising a fair, along with shipping and traveling costs need to be recouped. The only way this is sustainable is to price works with this recuperation in mind. I do think that the influence that art fairs have on the prices of contemporary art is a very serious issue – prices are inflated to make the business model feasible and are not necessarily based on fair market value. We have to participate in art fairs in order to promote the careers of the artists we represent, however I’m concerned about the real long-term advantages for artists and galleries. In many instances, my observation is that ‘the tail is wagging the dog’.

Given the under-developed local art markets across the continent, art fairs have become a crucial source of income for African contemporary art galleries and artists. They are also a platform for education, promotion and market development. Perhaps art fairs can become the better ‘devil you know’?

Art fairs are important marketing platforms but are unpredictable when it comes to sales. It’s a very risky business model to rely on the occasional four-day fair to make sales. To establish a sustainable art business that will support artists on a permament basis, a broad-based local and international market is essential. Education, promotion and market development should be a local focus if artists are to stand any chance of working and building their careers in their home countries. A recent problem is that art fair curators are becoming more and more prescriptive in terms of which artists’ works they want exhibited. What will happen then to the other artists represented by a gallery, who cannot show and make sales, at a particular fair?

How do you think that African artists and galleries can best leverage the current ‘moment’ for contemporary art from Africa?

My view is that all artists and galleries should have a thirty-year strategy, and not focus on the short-term. Artists’ lives depend on their long-term success – a ‘flash in the pan’ at one exhibition or fair won’t necessarily ensure that. The branding required to make a professional art career possible takes enormous effort, dedication and many years of producing good, authentic work – and of course the good luck of commercial success, which is determined by the buying public.

Given the infrastructural challenges, and that, with a few exceptions, local markets are unable to support artists’ livelihoods, we see more artists represented by galleries outside the continent and some of the best art from Africa ending up in foreign collections. Do you see this as a problem and if so, what do you think can be done to begin remedying it?

This is an economic and market reality and will only change as more Africans buy and collect African art. Growing local African art markets and supporting Africa’s artists requires the collective effort of all players – galleries, artists, collectors and governments. Education and exposure are key aspects – the abundance of artistic talent will only be appreciated, and artworks will only become desirable to own, if all involved subscribe to an orchestrated and long-term marketing strategy.

Johans Borman: During the apartheid era, South Africa was in cultural isolation. From the 1990s, our new democracy made it possible for South African artists to travel and exhibit internationally. This meant that local artists, curators, academics and students had the opportunity to experience international art trends and influences. From the mid-1990s, worldwide Internet access was the next major factor to counter South Africa’s cultural and geographic isolation. South Africa’s newfound democracy and political freedom meant international acceptance, which had a very positive influence on the local art market. It instilled confidence in South Africa’s future and brought new interest from local and international collectors and curators. The local art market expanded rapidly as new galleries opened, and the auction market boomed until 2001, when the 9/11 attacks stalled world markets.

So you don’t see the current focus on African contemporary art as a key change?

The South African contemporary art industry has experienced tremendous growth since the early 2000s, coinciding with the new international interest and focus on contemporary African art. The choice of the Zeitz Museum of Contemporary African Art to open in Cape Town reflects this sentiment and will potentially establish Cape Town as the future art capital of Africa.

You have written much about art as an asset class. Have you had to revise your ideas on the concept in the light of recent developments and trends in the market, especially in reference to the focus on emerging artists and phenomena such as flipping and speculation – which many say is here to stay? Is this fascination with emerging artists valid or are collectors missing the opportunity with more established artists who have remained under the radar or underexposed?

My views on living with and collecting art have not changed. I don’t see art as a typical financial investment instrument, as it’s not created to be that in the first place. We should never forget – art is about life and the art market is about money. Unlike conventional financial investments, art does not pay dividends, interest or rent. The ‘return on investment’ is the result of the interaction with a work of art – it lies in the emotional stimulation and ‘cerebral gymnastics’ experienced during this appreciation process.

In my opinion, the concept of ‘investment art’ or art as an asset class distracts from the real purpose of art. The concept is emphasised to motivate non-art lovers to spend more money in the ‘art industry,’ trusting that they will realise a healthy profit. This concept is largely promoted by auction houses and profit-driven dealers who create environments where speculation and flipping thrive. They don’t feel any responsibility towards maintaining a healthy and stable market – their sole objective is to realise a profit. These factors are definitely not beneficial to the careers of contemporary artists, as their livelihoods depend on a stable, long-term market for their work.

Contemporary art and emerging artists enjoy much publicity – particularly because most art fairs and publications focus on the contemporary market and are designed to promote the latest and ‘hottest.’ However, the reality is that the bulk of overall sales (in financial terms) come from the more established artists and works by artists from the Modern era. This confirms that seasoned collectors are still spending much more to own works by established, ‘branded’ artists who have a proven track record (in terms of prices and value.)

What about in the context of artists from across Africa coming to South Africa? My personal view is that it is a double-edged sword, in terms of career development and creativity. What is your view of this phenomenon?

Historically, artists have migrated to wherever they can establish sustainable careers. If not in their home countries, they will relocate to where they have an audience and buyers or collectors.

Art fairs have become the mainstay of the art market – a key channel to market. As a gallerist with an established practice and collector base, do you feel pressure to participate in these events?

The success of art fairs lies in the fact that they provide artists and galleries the opportunity to collectively generate public interest for (mostly) contemporary art. Art fairs, along with apps like Artsy, provide a one-stop opportunity to see and engage with the international art buying fraternity.

This one-stop opportunity does, however, come at an enormous cost. To make art fairs feasible, the additional costs of hosting, organising and publicising a fair, along with shipping and traveling costs need to be recouped. The only way this is sustainable is to price works with this recuperation in mind. I do think that the influence that art fairs have on the prices of contemporary art is a very serious issue – prices are inflated to make the business model feasible and are not necessarily based on fair market value. We have to participate in art fairs in order to promote the careers of the artists we represent, however I’m concerned about the real long-term advantages for artists and galleries. In many instances, my observation is that ‘the tail is wagging the dog’.

Given the under-developed local art markets across the continent, art fairs have become a crucial source of income for African contemporary art galleries and artists. They are also a platform for education, promotion and market development. Perhaps art fairs can become the better ‘devil you know’?

Art fairs are important marketing platforms but are unpredictable when it comes to sales. It’s a very risky business model to rely on the occasional four-day fair to make sales. To establish a sustainable art business that will support artists on a permament basis, a broad-based local and international market is essential. Education, promotion and market development should be a local focus if artists are to stand any chance of working and building their careers in their home countries. A recent problem is that art fair curators are becoming more and more prescriptive in terms of which artists’ works they want exhibited. What will happen then to the other artists represented by a gallery, who cannot show and make sales, at a particular fair?

How do you think that African artists and galleries can best leverage the current ‘moment’ for contemporary art from Africa?

My view is that all artists and galleries should have a thirty-year strategy, and not focus on the short-term. Artists’ lives depend on their long-term success – a ‘flash in the pan’ at one exhibition or fair won’t necessarily ensure that. The branding required to make a professional art career possible takes enormous effort, dedication and many years of producing good, authentic work – and of course the good luck of commercial success, which is determined by the buying public.

Given the infrastructural challenges, and that, with a few exceptions, local markets are unable to support artists’ livelihoods, we see more artists represented by galleries outside the continent and some of the best art from Africa ending up in foreign collections. Do you see this as a problem and if so, what do you think can be done to begin remedying it?

This is an economic and market reality and will only change as more Africans buy and collect African art. Growing local African art markets and supporting Africa’s artists requires the collective effort of all players – galleries, artists, collectors and governments. Education and exposure are key aspects – the abundance of artistic talent will only be appreciated, and artworks will only become desirable to own, if all involved subscribe to an orchestrated and long-term marketing strategy.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed